1917: An Agonizing Sequence Shot

1917 was heralded as one of the top favorites for the Most Valuable Oscar award. He nevertheless had to be satisfied with the statuettes rewarding the most technical part. The Parasites were undoubtedly the real eye-opener, a film that made history and won the most coveted awards.

Talent does not distinguish between languages or borders. This was confirmed by the historic awarding of the Best Picture Award to a South Korean film. However, we will talk about another of the big favorites below. A film that triumphed at the BAFTAs and the Golden Globes, but not so much at the Oscars.

” loading = “lazy” width = “500” height = “281” src = “https: // www.youtube.com/embed/0YwR8n9tqXM?feature=oembed “frameBorder =” 0 “allow =” accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture “allowfullscreen =” “]

A somewhat forgotten past

Countless feature films have been made about WWII and even Vietnam. Few of the internationally successful titles, on the other hand, were inspired by the First World War. Perhaps one of the best known is the unforgettable Stanley Kubrick’s Paths of Glory with recently deceased Kirk Doulgas.

The First World War raises more doubts than the Second. It is also not as cinematographic as the latter. The enemy is perhaps not sufficiently clear and the chaos which characterized it hindered, in a certain way, its adaptation to the cinema.

Any spectator who refers to the cinema of war will inevitably cite titles in which the clear enemy is none other than Nazism.

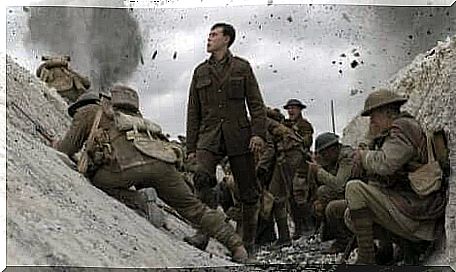

Sam Mendes, inspired by the stories his grandfather told him, dares, through a simple story film and a sublime staging, to immerse himself in the trenches of the Great War.

Activate the right levers

A joke can be told in different ways and depending on who tells it and how it is told, it will make us laugh out loud or not. This statement, as simple as it may seem, can be applied to cinema and, ultimately, to art.

The message is fundamental, there is no doubt. If the backstory doesn’t touch us, maybe there’s not much we can do. But, like all jokes, the storytelling is essential.

The plot of 1917 could not be simpler: two simple soldiers of the British army must transmit a message to another troops to prevent the enemy from killing them.

This is when something as simple as a message comes to life and gains public empathy. An audience that maintains sepulchral silence because it feels its oppressed heart and its nerves on edge in the face of a danger as imminent as death.

The cast of the film includes some big names in British cinema from the last decades, such as Colin Firth or Bennedict Cumberbatch. He nevertheless leaves all the responsibility for the main roles to two young strangers.

It is true that another type of storytelling would have left more room for the aforementioned secondary characters and actors. The decision to rely on a reduced number of protagonists, however, allows the public to fully participate in the action.

The trenches never looked so shocking, so poetic and so stifling at the same time. The viewer can perceive terror, loneliness and desolation. And all this thanks to an impeccable technique that takes root in the suspense. How is it possible ? Through the use of an eternal and illusory sequence shot.

1917 and a false sequence shot

1917 did not invent anything absolutely new since Hitchcock himself experimented with La Corde in 1948 the limits of the cut. Other more recent films, such as Birdman (Joaquin Oristell, 2015) or Victoria (Sebastian Schipper, 2015), also use this technique.

They thus combine and explore the possibilities offered by new technologies with a technique that we already know. A success which makes the spectator identify fully with the protagonists and perceive the action in “real time”.

However, interpretation and technical work require more effort. Indeed, everything must be perfectly millimeter and calculated, even the atmospheric conditions, when shooting with such long shots.

The illusion of the sequence shot with its millimetric and almost imperceptible cuts gives us, as spectators, this feeling of anguish. We are no longer passive spectators of a tragedy, but accomplices.

Like the protagonists, we also cannot escape. The use of natural light, spaces, faces and subtle special effects emphasize the action.

The viewer ends up feeling trapped in the labyrinth of trenches, empathizing with the protagonists and feeling fear through the screen.

Music and image generate a frightening beauty in which energy is the key. The camera never looks back. She never comes back. She moves forward with the characters’ footsteps and the music appears in moments of greatest tension, partly reminding us of Hitchcock.

The complexity of 1917 lies precisely in the difficulty of knowing how to take advantage of natural resources, the play of chiaroscuro, natural light and the immediacy that it intends to convey, not to mention a team that succeeded in recreating a hostile scene. full of trenches in which countless young men lived and died in a war which, as always, was absurd.

1917: a cinematic experience

The feeling of watching a movie without a break, even if it is an illusion, generates uncertainty in the viewer. Tragically fostered uncertainty with the film’s longest, most obvious, and most thoughtful cut.

After receiving a bullet, we find ourselves in darkness, an eternal darkness which, far from relieving us, increases our anxiety. Is it over? Will we now see cut scenes? Absolutely not. The drastic cut only serves as a point and followed by a story that still has a lot to tell. A story that takes on other infinite and suffocating plans.

The film won ten nominations for various grand prizes, but only received three statuettes. Those relating to technique, also important. A movie is nothing without a solid script.

However, it cannot come to life exclusively through the script. From costumes to music, from performance to photography, cinema is a complex art. It is indeed a difficult teamwork in which all the elements are important, fundamental.

This is probably one of my less unbiased articles. Nevertheless, as in all criticism and in all art, taste plays a fundamental role. I am indeed not passionate about war cinema which becomes anti-war. I am a great admirer of Mendes and Roger Deakins (the genius in charge of photography from 1917 ).

Mendes captivated me with American Beauty , hypnotized me and invited me to dive into a film which, without too much surprise, took me fully and continues to fascinate me today. He managed to show me the beauty of a simple plastic bag and now manages to overwhelm me and find beauty in an extremely hostile environment.

All this staging to tell us something that we already know. Something that the cinema has repeated over and over again: wars are absurd; the human being is absurd while nature takes its course.

Because drowning while cherry blossoms has never been more meaningful. To see death where life arises or to see human destruction in a natural environment that struggles to flourish is poetic, cathartic and revealing.

Nature acts as an additional character, alien to humans, but omnipresent. The tree rises as the most significant symbol. A tree present at the beginning and at the end, which makes this film somewhat cyclical.

Beyond the technical details, 1917 is a lesson in humanity. A clear tribute to those who lived through the Great War, to those who saw death in their hands and their illusions buried in the mud.