To The Guard: Monsters Do Exist

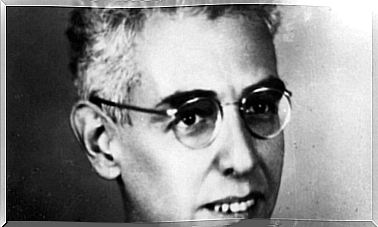

On February 22, during the 44th Cesar ceremony, the drama on macho violence Until the Guard, director Xavier Legrand’s first film, won the statuette for best film. And this is not surprising. This film appeared out of nowhere to hit us hard by tackling an extremely deep social subject.

The director gives us the details of shared custody. We spectators remain frozen in our cinema room. We find that monsters exist: they live in houses, among families, and not in dark and isolated places. They can be next to us, and this idea is even more disturbing.

To the Guard : the monster

The story is presented to us through an examining magistrate who deals with a divorce and shared custody case. It is difficult to get a full picture of the case, although some of the more notable elements seem obvious, such as the violence exerted by the father on his wife.

It is from there that everything seems more confused and that justice seems to slip. There should be no doubts in the face of a simple question: is it okay or not to force a child to spend time with the abuser of his mother?

Miriam’s lawyer describes a particularly possessive and violent man. Antoine’s lawyer refutes these points and says that it is abnormal for Miriam to want to prevent Antoine from showing all the love he feels for his children.

For the mother’s lawyer, it is difficult to find real evidence on the real character of the father. Because if there is one thing that an abuser knows how to do, it is to adapt his behavior to his interests according to the situation. However, the veil over the protagonists’ true personalities will eventually lift as the film goes on.

From the court ruling, which establishes shared custody, we can guess that disaster is going to happen. A slow explosion of violence, repression and anguish permeates the screens through the masterful interpretation of Thomas Gioria who plays Julien, the youngest of the family.

From court decision to shared custody hell

From the moment the father (Denis Ménochet) begins his custody, a climate of tension sets in. A close-up of the face of the terrified child; a dialogue without words capable of tense you up and transmitting a feeling of suffocation.

The child’s gaze and his expressions express everything he has experienced, everything he has felt. The absence of music makes the sounds of everyday life resonate like threats. A key that opens a door, that sound that triggers real fear for many abused women.

We realize that we are not dealing with a case of parental alienation, a diagnostic label of questionable scientific reliability. The narcissistic pervert Antoine sometimes knows how to show himself as a misunderstood being, who could almost be a victim. A victim because he loves his family.

Monsters do exist

No one in the family believes in this role played by the father. Everyone knows that his reconciliations are not synonymous with remorse. This is just one way to regain the control it has lost. The great strength of the film lies above all in the way in which the director, Xavier Legrand, leaves us breathless by relying on a mixture of fear and hope, a slightly perverse mixture.

We’re guessing that a very strong scene is going to take place, to put an end to all the tension and frustration built up by the father. A father who does not manage to get closer to his terrified wife through this shared custody. The latter lives by hiding and lying to him to avoid any type of aggression.

The father’s strategy to get closer to his wife Miriam (Léa Drucker) through the intimidation of the little one seems to have failed. But we know that frustration is a component to consider because it often precedes anger and violence.

This is where we start to hear the doorbell, a constant noise that terrifies us. We don’t know how the abuse unfolded, but we feel it happened frequently.

Social responsibility

The unfolding of history only anticipates disaster. We can only attribute the qualifier of “devastating” to it. The protagonist clings to a hope, that the noise of the doorbell stops. She knows it’s there, she knows it will ring for a long time to come.

This noise will stop and others will start to indicate that this time Antoine is not ready to stop. The last scene in this film is terrifying. She doesn’t need any special effects or gloomy makeup. The protagonist no longer looks like a human being but a beast blinded by pride and revenge.

The reality is so strong that the empathy we feel for this mother and her child ends up being painful. We are that neighbor who warns that something is happening. This policeman who gets this phone call trying to deal with the situation as best he can.

Monsters exist, they live in the midst of families and not in isolated and gloomy corners. They can even take our name. We cannot fight them with cognitive behavioral therapies: it will only come later.

These monsters, we fight them with the force of education, the sword of empathy, the badge of solidarity, the glove of justice and the application of an intervention.